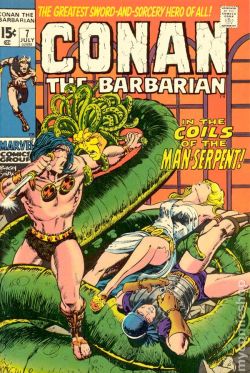

In 1970, Marvel Comics, having bought the rights to the character of Conan, released the first issue of Conan the Barbarian to great approval from its fan base, the series quickly becoming so popular that it would produce a feature film within a decade. D.C. Comics, Marvel’s rival, saw Conan as a threat to their own comic empire, and began a number of different comic series which they would hope to unite under the banner of a “Sword and Sorcery” line to compete with Marvel. To challenge Conan D.C needed their own barbarian, so they set about reimagining Beowulf in the same vein. Beowulf: Dragon Slayer, first released in 1975, was one of the first of such attempts to piggyback off Marvel’s success.

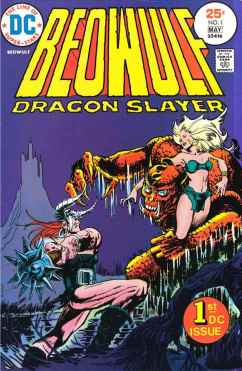

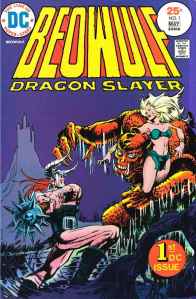

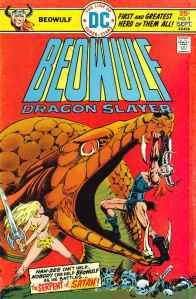

This is immediately apparent merely by looking at the cover page of Issue #1. Beowulf: Dragon Slayer is everything Conan is and everything the original poem is not. Beowulf swings an oversized mace at Grendel, who is carrying a bikini-clad Amazonian love interest in need of Beowulf’s saving, while in the background stands an imposing mountain fortress that is supposed to be Heorot. Dressed in a loincloth and horned helmet, Beowulf is the quintessential barbarian, nearly a spitting image of Conan himself, down to the clothing and the damsel in distress. D.C. apparently thought copy-pasting Conan into a slightly different universe would be the easiest way to appeal to Marvel’s audience. While the comics claim to be an adaptation of the Old English poem, and while the poem’s influence is certainly there, the end product is far removed from its source and much more resembles Conan than it does Beowulf.

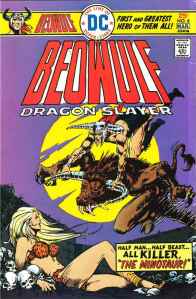

In the poem, Beowulf fights Grendel hand-to-hand—“I will carry neither my sword nor my broad golden shield, but instead I will grapple with my enemy” (412-4)—Heorot is a hall, not a castle, and no such eye-candy exists. I would be hard pressed to find an image that better sums up stereotypical comic tropes than this front page, particularly those of medieval comic book imaginings. Indeed, the similarities to Conan and the deviations from the poem become further apparent when examining the character of Beowulf, the “Conan” of this series. In the original poem, Beowulf is both a capable warrior and a capable leader, strong enough to defeat the world’s greatest monsters and intelligent enough to lead his Geats to years of prosperity. While he is never presented as a great intellectual, he is always well within control of whatever situation he comes across, from pure feats of strength to navigating political waters. In the comics, Beowulf is nothing more than a hulking barbarian, even described by Hrothgar as resembling, “one of those ape-beasts . . . brought back from the Darklands!” Additionally, Nan-Zee, the “capable” warrior who always finds herself in need of saving, upon first meeting Beowulf calls him “my mindless barbarian.” In the comics, Beowulf is a man who sees every problem as needing to be clubbed in the head until things work themselves out, one series of mindless action and violence after another, one monster after another to be faced and defeated.

However, this begs the question: If all D.C. wanted was a barbarian to compete with the likes of Conan, why draw from Beowulf and not just create a bog-standard hero-barbarian?

The answer, it seems, comes from a letter from the author included on the final page of Issue #1. This letter, addressed to the reader, encourages all people who come across this comic to read it because, the author claims, it seamlessly combines the old Beowulf text with more modern conventions of action, adventure, and pop culture in an educational manner. The author even encourages students to read it in class and when questioned by their teachers to assure them that it is an educational piece above all else. He even goes so far as to say, “For the field of education is the place where comics can do the most good,” and, “We’ll try our best to produce a book that you’ll be proud to bring your classroom and show your teacher.”

It would seem from this letter that the author aspired for his comic hero to be more than a mere Conan impersonator and that he wanted it at least to appear as if it were something beyond mindless, visceral action. The writer actually claims that, “if we kept to the original ‘educational’ poem, the comic book would be unbelievably gory,” meaning that the violence in the comic book has, in fact, been toned down rather than sensationalized. The author tries to make Beowulf the “thinking-man’s Conan,” granting both the comic book and D.C. some intellectual cache by drawing from a highly regarded literary text.

Nevertheless, the comics, for all their attempts to be Conan, do draw some things from the original poem, at least in Issue #1. In particular, the comic retains some of the characters’ motivations. Grendel, for example, is the first character introduced, a stuttering behemoth and a hulking beast that is not quite human but not quite fully monster. He is ascribed the same motivators as he has in the poem: he cannot stand to hear the merriment of men in “Castle” Heorot. As he grows enraged, a spark appears in Grendel’s eyes in the final panel. This indicates that he is not merely some automaton lacking emotion, but gives us a glimpse of his underlying psyche—he is excited, filled with a blood-lust that can only be quenched by blood, leaving a silence in his wake.The way Grendel himself is represented, on the other hand, differs somewhat from the way I had originally pictured him while reading the poem. He rises up menacingly from the waters of his swamp, the angle from which we view his hulking figure clearly meant to show his imposing strength as something beyond human. The scales he is drawn with in the second to last panel are also an interesting touch, making him appear more like a “swamp-creature” than I had originally thought. What really throws me a bit in his appearance, however, is his coloring. I had always imagined Grendel, a nightmare that attacks at night, as being a dark, menacing figure who would be able to blend in with the shadows; indeed, he is described in the poem as being “sheltered by the dark” (89). In the comics, he is bright orange-red, most likely in order to emphasize the demon side of Grendel, demons generally being colored red to match the fires of Hell, especially given the coming subplot between Grendel and his master, Satan, the great demon himself. Before we even meet Satan in Issue #2, Grendel’s coloring alongside his battle cries “For Satan” emphasize this connection.

men in “Castle” Heorot. As he grows enraged, a spark appears in Grendel’s eyes in the final panel. This indicates that he is not merely some automaton lacking emotion, but gives us a glimpse of his underlying psyche—he is excited, filled with a blood-lust that can only be quenched by blood, leaving a silence in his wake.The way Grendel himself is represented, on the other hand, differs somewhat from the way I had originally pictured him while reading the poem. He rises up menacingly from the waters of his swamp, the angle from which we view his hulking figure clearly meant to show his imposing strength as something beyond human. The scales he is drawn with in the second to last panel are also an interesting touch, making him appear more like a “swamp-creature” than I had originally thought. What really throws me a bit in his appearance, however, is his coloring. I had always imagined Grendel, a nightmare that attacks at night, as being a dark, menacing figure who would be able to blend in with the shadows; indeed, he is described in the poem as being “sheltered by the dark” (89). In the comics, he is bright orange-red, most likely in order to emphasize the demon side of Grendel, demons generally being colored red to match the fires of Hell, especially given the coming subplot between Grendel and his master, Satan, the great demon himself. Before we even meet Satan in Issue #2, Grendel’s coloring alongside his battle cries “For Satan” emphasize this connection.

While Beowulf’s character may have been made to resemble Conan, his motivations, much like Grendel’s, also make the transition relatively intact. The final line of the original poem is that Beowulf was lof-geornost (“most eager for fame”). The comic places a great emphasis on this as well. In one of the first instance of dialogue not occurring during battle, Wiglaf, a Geatish companion to Beowulf who appears in the latter part of the poem, asks Beowulf why they are sailing to Daneland. Beowulf responds that he seeks lof, fame, which drives him so much that he wants to aid the Danes, the sworn enemy of the Geats, so that he can earn it. The speech bubble in which Beowulf first utters the word lof is placed almost directly in the middle of the page, which, along with the conversation occurring near the comic’s beginning, illustrates importance as a central component of Beowulf’s being. He goes on to say, “That fame will keep the spirit of Beowulf alive centuries after I am dust!”, further emphasizing the importance he places on this earthly glory as it is the only thing that can keep him alive in this “impermanent world.” Impermanence, which can also be referred to as the transitory nature of life, is critically important to the poem, as, among other things, evokes the tension between the clashing cultures of pagans, who dream of earthly glory, and Christianity, which says that earthly glory matters little in the grand scheme of things.

Grendel’s, also make the transition relatively intact. The final line of the original poem is that Beowulf was lof-geornost (“most eager for fame”). The comic places a great emphasis on this as well. In one of the first instance of dialogue not occurring during battle, Wiglaf, a Geatish companion to Beowulf who appears in the latter part of the poem, asks Beowulf why they are sailing to Daneland. Beowulf responds that he seeks lof, fame, which drives him so much that he wants to aid the Danes, the sworn enemy of the Geats, so that he can earn it. The speech bubble in which Beowulf first utters the word lof is placed almost directly in the middle of the page, which, along with the conversation occurring near the comic’s beginning, illustrates importance as a central component of Beowulf’s being. He goes on to say, “That fame will keep the spirit of Beowulf alive centuries after I am dust!”, further emphasizing the importance he places on this earthly glory as it is the only thing that can keep him alive in this “impermanent world.” Impermanence, which can also be referred to as the transitory nature of life, is critically important to the poem, as, among other things, evokes the tension between the clashing cultures of pagans, who dream of earthly glory, and Christianity, which says that earthly glory matters little in the grand scheme of things.

Even while the comic manages to accurately invoke certain aspects of the poem and Anglo-Saxon culture more broadly, it fails to function as a faithful adaption. The original poem maintained a balance between the monstrous and the human, and that is what lends it much of its intrigue. Beowulf is both monster slayer and politician, displaying great physical strength in one instance and in the next showing the wherewithal to lead his people. In one scene pagan and Norse mythologies are referenced, and in the next the poet is describing the role of God as Beowulf battles Grendel’s mother. There is always some form of tension that can’t be resolved merely by swinging a sword, but rather that must be considered and worked through by the reader.

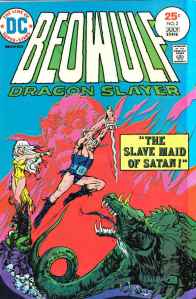

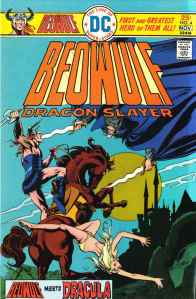

As an adaption, this is what I think the comics truly lack—they are a straightforward hack-and-slash adventure series. Beowulf goes to aid Hrothgar not because he wants to help him, but  forfame and fame alone. He is only ever shown with his small group of companions, and there is no indication that he would make a good political leader. Indeed, the first alliance he has a chance to form, with Nan-Zee, he approaches by blatantly insulting her—“You?!? A warrior? A woman warrior? Ha-Ha-Ha-Ha-Ha! And a Swede no less!” There is also none of the religious tension that existed in the poem. Satan is made into a literal character in Issue #2, taking an unspoken tension and making it physical so that Beowulf has yet something else to swing away at, a mindless hero and not the noble warrior portrayed in the poem.

forfame and fame alone. He is only ever shown with his small group of companions, and there is no indication that he would make a good political leader. Indeed, the first alliance he has a chance to form, with Nan-Zee, he approaches by blatantly insulting her—“You?!? A warrior? A woman warrior? Ha-Ha-Ha-Ha-Ha! And a Swede no less!” There is also none of the religious tension that existed in the poem. Satan is made into a literal character in Issue #2, taking an unspoken tension and making it physical so that Beowulf has yet something else to swing away at, a mindless hero and not the noble warrior portrayed in the poem.

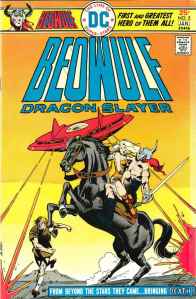

The thing is, there is nothing wrong with fun adventure romps. These comics are just as mindless as Conan the Barbarian, but that doesn’t make Conan bad, nor does it necessarily make the Beowulf: Dragon Slayer comics bad. There is a place for mindless fun, and comics serve that medium quite well. The problem is that the subject of these comics is Beowulf. Conan could act as a barbarian because that’s what his character was, but Beowulf is decidedly not a barbarian in the original poem. In order for him to become a Conan-type figure, the comics needed to manipulate his character so much that he is almost unrecognizable. If the comics were simply a hack-and-slash version of Beowulf’s adventures, perhaps that would have been, if not accurate, then at least acceptable. But the comics in the following issues leave their source so far behind that it isn’t even on the horizon, as Beowulf does things such as getting abducted by Egyptian aliens as Grendel plans to and succeeds in killing Satan. The further one goes, the more apparent it is that this “adaptation” draws much more from Conan that it does from Beowulf.

I think whether or not one should take a look at Beowulf: Dragon Slayer really comes down to what your opinions are on bad media. These comics are like the kind of movie that you’d describe as being so bad that’s it’s good, it’s miscues so amazing that they become unintentionally hilarious. To be able to view them in this manner, though, I had to look at them not expecting them to do Beowulf any real justice and just let their crazy flow of events take me away. If you can do that, then they’re definitely worth checking out. But, if not, do yourself a favor and stick to the poem.

—Ben Warner ’15 is a Physics-turned-English major who has taken more than his fair share of Philosophy and Classics courses. His love of unintentional comedy makes it no wonder than an old 1970s comic book would capture his attention.