Gareth Hinds’ Beowulf: A Dragon Chasing Its Tail

In Gareth Hinds’ 2007 graphic novel adaptation of Beowulf, the reader is introduced to Beowulf’s greatest antagonist in an epic centerfold image: a ferocious dragon that lays atop a pile of treasure, tail in its mouth. While this particular adaptation has not been subject to extensive criticism, it is shocking to me that this has been entirely overlooked. The image of a dragon eating its tail is identical to the image of the “Ouroboros,” an image rooted in ancient Egyptian folklore–one that represents birth and rebirth–the general cyclical nature of existence. While I can’t speak to Gareth Hinds’ intent, I will argue that this image serves as a metatextual acknowledgement, not only of the way in which Beowulf has been born and reborn repeatedly over the course of endless translations across various media, but of the daunting challenge that it is to re-adapt this text yet again with pen and paint. So here’s the question: is Hinds’ adaptation a good one? Is this dragon creeping forward or merely a beast chasing its own tail?

Graphic novelist Gareth Hinds has made a name for himself translating canonical classics ranging from Homer’s The Odyssey to Shakespeare’s King Lear, from prose and poetry into the oft misunderstood medium of comics. In doing so, he makes palatable for young adults dense poetry and epic prose by shifting the narrative weight from text to image. In fact, the exciting battle sequences in Hinds’ adaptation occur without any text whatsoever. As an avid reader, I’m all for the introduction of timeless literature to a younger set, but it’s hard to read these adaptations without yearning, at least a bit, for the substance of the original text.

Hinds’ 2007 adaptation of Beowulf posed a particular challenge to the graphic novelist. How does one adapt something so well-loved and so frequently adapted without treading ground previously trod? The answer, in short, is… well, like this. The critical response to Hinds’ adaptation has looked at the text not as a Beowulf translation per se, but instead as a fun book for teens. On his site, Hinds includes a quote from the New York Times that calls the book “A first-rate horror yarn… Hinds stages great fight scenes, choreographing them like a kung-fu master… Visceral.” Elsewhere, the Kirkus review complains only that “the action is sometimes hard to follow” and primarily compares the text to existing adaptations. While these remarks are on-point and critique the graphic novel as an independent work, I intend to discuss Beowulf in relation to the original poem. While the graphic novel necessarily omits certain aspects of the original poem, it is generally a good, visually rich adaptation. With Hinds behind the wheel, the action is visceral, the laughs are genuinely funny, and the world of Anglo-Saxon England is, well, exciting.

Beowulf is a challenging poem. Even for a strong reader with an excellent translation, Beowulf is not an easy read on the first go. In the first seventy lines alone we are introduced to numerous characters with names like Scyld Scefing, Beow (who, mind you, is not Beowulf), Healfdane, and Heorogar. These names come not with the detailed descriptions of personality and appearance with which we’ve grown accustomed in modern prose. Instead, names and locations appear quickly before disappearing into a whirlwind of narrative exposition. The best thing about Gareth Hinds’ graphic adaptation of Beowulf is the way in which Hinds calms the storm, organizes its constituent parts with beautiful illustrations, and allows readers to return to the original poem with a finer, more spatially-organized understanding of the text.

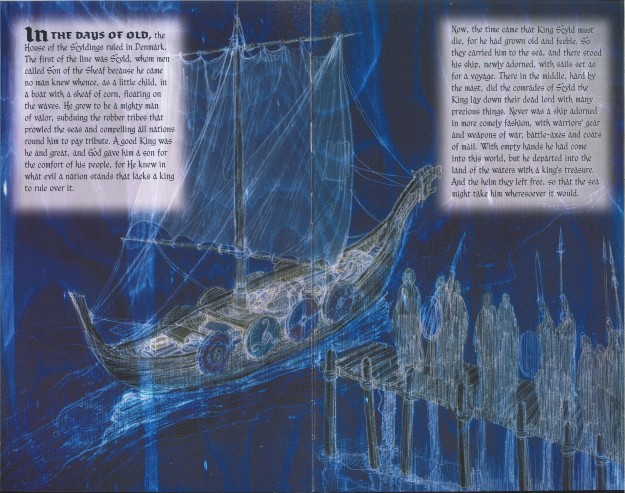

Like the poem, the graphic novel opens with the death of Scyld Scefing. Gareth Hinds employs a ghostly drawing style exclusively for Scyld’s introduction. Nowhere else in the book do we see this matte of deep blue sea accented with spectral white pencil sketches as we do of Scyld’s warriors at his sea funeral. In addition to the text on the page, the image makes immediately clear to the reader two things: Scyld Scefing was an exceedingly good king and his spirit and the gravity of his death haunt the remainder of the poem. In short, Hinds makes clear that this is a text concerned with death. And if we look further, we will see that the text itself, much like its endless adaptation across various media, is a sort of Ouroboros–one that opens and closes with striking images of death.

The images in Gareth Hinds’ Beowulf do not simply reflect the poem’s serious thematic conceits, however, because doing so would be a disservice to the remarkable tonal range of the original poem. Anglo-Saxons had a sense of humor, a fun fact that often goes unnoticed in scholarly criticism, and Hinds’ illustrations imbue Beowulf with a sense of humor and wonder that one might miss when simply reading a translation of the poem. And often, these appear in subtle images. One particularly successful representation of a scene in the poem is Unferth’s questioning of Beowulf’s physical prowess as he accuses Beowulf of losing a swimming contest. After providing his own account of the events, Beowulf replies: “Unferth, my friend, you have told us / all about Breca and his expedition, / but you have spoken after drinking too much beer” (506-509). Now this line is humorous in the poem because Beowulf is at his most amusing when he is arrogant and dismissive, but Hinds pairs this with a hilarious image. Immediately following Beowulf’s rebuttal, several rowdy Vikings throw a horn at Unferth’s head which results in a classic “THONK!” and is followed by raucous laughter. This slapstick addition provides a humanizing moment in the text as it portrays the indiscretion of even privileged members of the court. Unferth steps over the line and Beowulf quickly puts him back in his place.

One of the most visceral scenes in the entire text, however, is one that is easily overlooked in  the original poem. When Beowulf and his men travel to the moor to slay Grendel’s mother, they happen upon a large water monster. Here, Hinds takes creative liberties with the fantastic world of the original poem and the Anglo-Saxon fixation on water-dwelling beasts to insert a brief, but exciting encounter. The men arrive lakeside and see a long neck craning out of the water that looks an awful lot like the legendary monster of Loch Ness. Almost immediately one of the warriors shoots an arrow through its head as the other men run it through with their spears. Their quick disposal of the beast illustrates better than any other scene that Beowulf and his men are an exceptional bunch–an Anglo-Saxon A-Team, if you will. It is these truly exciting moments that remind the reader of the adaptive potential of Beowulf.

the original poem. When Beowulf and his men travel to the moor to slay Grendel’s mother, they happen upon a large water monster. Here, Hinds takes creative liberties with the fantastic world of the original poem and the Anglo-Saxon fixation on water-dwelling beasts to insert a brief, but exciting encounter. The men arrive lakeside and see a long neck craning out of the water that looks an awful lot like the legendary monster of Loch Ness. Almost immediately one of the warriors shoots an arrow through its head as the other men run it through with their spears. Their quick disposal of the beast illustrates better than any other scene that Beowulf and his men are an exceptional bunch–an Anglo-Saxon A-Team, if you will. It is these truly exciting moments that remind the reader of the adaptive potential of Beowulf.

While Gareth Hinds does an admirable job of seizing upon the humor and world-building potential of the original work, he also occasionally does a damned good job of representing the poem’s more iconic moments. And what’s a Beowulf comic book without a stunning Grendel fight?

Here the Grendel fight is long and incredibly violent. We see only a silhouette creep into the hall of Heorot before Grendel grabs a soldier by the neck, bites his head off, and drinks the blood as it gushes from the wound. Before he can finish eating, however, Beowulf appears. Hinds does a brilliant job of visually reinforcing the original text’s suggestion that Beowulf and Grendel are monstrous equals. While the graphic novel retains the poem’s moment in which Beowulf and Grendel lock grips in a moment of uncanny unity, it inserts a beat just before that in which Grendel and Beowulf lock eyes–an image that Hinds represents with two symmetrical panels depicting their respective stares. In this way, the two are visually figured as equals. They then tumble about for nine pages as Beowulf performs various wrestling moves on Grendel before delivering a fatal kick to Grendel’s head which then explodes on the walls of Heorot.

of Heorot before Grendel grabs a soldier by the neck, bites his head off, and drinks the blood as it gushes from the wound. Before he can finish eating, however, Beowulf appears. Hinds does a brilliant job of visually reinforcing the original text’s suggestion that Beowulf and Grendel are monstrous equals. While the graphic novel retains the poem’s moment in which Beowulf and Grendel lock grips in a moment of uncanny unity, it inserts a beat just before that in which Grendel and Beowulf lock eyes–an image that Hinds represents with two symmetrical panels depicting their respective stares. In this way, the two are visually figured as equals. They then tumble about for nine pages as Beowulf performs various wrestling moves on Grendel before delivering a fatal kick to Grendel’s head which then explodes on the walls of Heorot.

There is one plot point, however, that is egregiously omitted and that is the poem’s final suggestion of impending doom. In the original poem, after Beowulf dies, his men fear that they will be attacked by the Swedes when they learn of the brave hero’s death. This is an essential plot point as it gives more gravity to the hero’s death and also reinforces Beowulf’s identity as protector. The text begs the question: without Beowulf, can his people survive?

In Hinds’ Beowulf , the titular character dies leaned up against a sea wall. Right before he passes, he accepts his fate: “Death has taken all my kinsmen into his keeping, and now I must needs follow them.” While this moment possesses the requisite gravitas of any good final beat, it fails to acknowledge that Beowulf is not really the last kinsman to die. In fact, his death will potentially lead to the annihilation of his people. To disregard the implications of his final act of hubris is to miss one of the poem’s most important lessons. Some will argue that this moral is less applicable to a contemporary audience, but I would argue that, as corny as it may sound, the virtues of selflessness are timeless.

he accepts his fate: “Death has taken all my kinsmen into his keeping, and now I must needs follow them.” While this moment possesses the requisite gravitas of any good final beat, it fails to acknowledge that Beowulf is not really the last kinsman to die. In fact, his death will potentially lead to the annihilation of his people. To disregard the implications of his final act of hubris is to miss one of the poem’s most important lessons. Some will argue that this moral is less applicable to a contemporary audience, but I would argue that, as corny as it may sound, the virtues of selflessness are timeless.

Beowulf is a story of ego, humanity, and the cyclical nature of violence. Gareth Hinds’ Beowulf, while not quite capturing the full weight of the original poem, does justice to its characters and major set pieces through its beautiful drawings and evident love for its Anglo-Saxon world. If we are to evaluate Hinds’ graphic novel in direct comparison to the original poem, we realize that, while Hinds’ Beowulf should not stand in for the original poem, it is still an excellent visual companion. Hinds’ Beowulf is a tail that will likely be devoured and eventually replaced with yet another graphic retelling of the original poem, but for now, this one will do just fine.

–Thomas Grabinski ’15 is an English major, film fanatic, and music nerd. Since all of the films were spoken for and since Beowulf never made a record (as far as he knows), he opted to review this comic because he also likes comics.

Note from TDA: Thomas directed and edited the Old English “Wake Me Up” video.